This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Why we shouldn't be so quick to demonise bats

Australian health authorities regularly issue public reminders not to touch bats because they can host Australian Bat Lyssavirus (ABLV). This type of health education is necessary because it reduces human exposure to bat-borne diseases. However, subsequent sensationalist media reporting risks demonising bats, which increases human-wildlife conflict and poses barriers to conservation.

Bats are remarkable native creatures of key ecological and economic importance. We urgently need more matter-of-fact style reporting around the risks of bat-borne diseases to avoid vilification and persecution of these unappreciated mammals.

Read more: In defence of bats: beautifully designed mammals that should be left in peace

Australia’s weird and wonderful bats

Australia has 81 bat species, from nine families. They comprise the second-largest group of mammals after marsupials (159 species). They range in size from the little-known northern pipistrelle that weighs less than three grams and ranks amongst the smallest bats in the world, to the black flying-fox that can weigh more than a kilogram and is among the world’s largest.

Bats play many different roles in Australian ecosystems. The southern myotis or “fishing bat”, for example, has long toes that it uses to rake up small fish and invertebrates from rivers, lakes and ponds. The golden-tipped bat delicately plucks spiders from their webs, while the ghost bat feeds on large insects, rodents, birds, and even other bats. These are examples of “microbats” — species that use echolocation to find their way in darkness and detect prey.

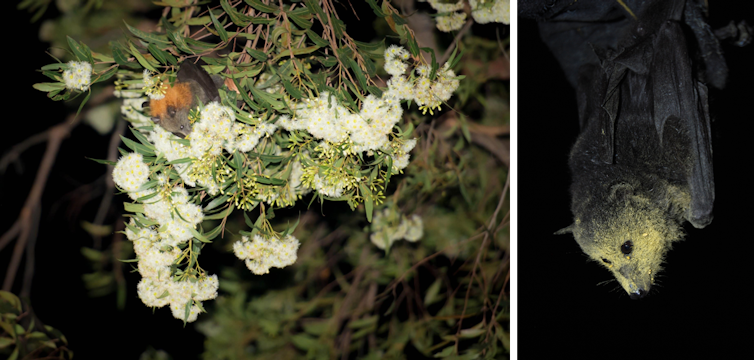

Australia is also home to nine “megabats” — species that rely on large eyes and a keen sense of smell to find pollen, nectar, or fruit. The common blossom bat, for example, is a mouse-sized fruit bat with a very long tongue for feeding on nectar; the eastern tube-nosed fruit bat is a solitary bat with long tubular nostrils that are thought to prevent fruit juices from running up its nose; and the little red flying fox is adapted for long-distance flight, travelling thousands of kilometres across the Australian landscape in search of food.

Bats are largely nocturnal and inconspicuous, except for those flying-foxes that sometimes appear in large numbers in urban environments where they can be cause for much frustration and conflict.

Read more: Not in my backyard? How to live alongside flying-foxes in urban Australia

All bats are vulnerable to a range of human threats, including the clearing of foraging areas and the loss or disturbance of roosts. Thirteen of Australia’s bat species are now listed as “threatened” under our national conservation legislation. Australia’s most recent extinction was a bat: the Christmas Island pipistrelle winked out of existence forever in 2009 following a sluggish federal government response to calls for urgent conservation action.

Why are bats important?

Bats are important in two ways. First, each species has its own value as a part of Australia’s natural and cultural heritage. They are fragile creatures, but tough enough to survive and thrive in the harsh Australian bush — if they are given the chance.

Second, microbats provide valuable ecosystem services because many are voracious predators of insects, including many agricultural and forestry pests. Megabats, meanwhile, provide long-distance pollination and seed-dispersal services, helping to maintain the integrity of Australia’s increasingly fragmented natural ecosystems.

Australian bat lyssavirus

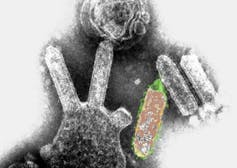

Some Australian bats are hosts for Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV) that can cause a rabies-like disease in humans and potentially pets. Since its discovery in 1996, there have been three human deaths from ABLV in Australia.

The virus is rare, and its prevalence among bats is thought to be less than 1%. But it is more common among sick, orphaned, or injured bats – that are in turn more likely to end up in hands of the public.

A rabies vaccine has been around since the time of Louis Pasteur, and when combined with proper wound management and prompt medical care, is very effective in preventing the disease. Rabies vaccine that is given after exposure to ABLV, but before a person becomes unwell, can still prevent the disease. But once a person develops the disease there is no effective treatment.

“No touch, no risk”

As long as we do not touch bats we are not at risk. Yet despite this simple message, many people still handle sick or injured bats, even though this is the major cause of potential exposures to ABLV.

Humans are not exposed to ABLV when bats fly overhead or feed or roost in gardens. Bat urine and faeces are not considered to be infectious, and tank or surface water contaminated with these substances is also not a threat.

The primary ABLV transmission route is through bites or scratches, bringing infected bat saliva into direct contact with the eyes, nose or mouth, or with an open wound. Therefore, the best protection by far is to avoid handling bats.

If you do get scratched or bitten by a bat, the Australian Department of Health recommends that you immediately wash the wound thoroughly with soap and water for at least five minutes, apply an antiseptic with antiviral action, and seek medical attention.

Prevention is better than cure, so people should never handle bats (or other wildlife) unless they are trained, vaccinated, and wearing appropriate protective gear. If you find an injured or sick bat, the best thing to do is to contact your local wildlife agency or veterinarian.

Reporting without the demonisation

Bats already have a dark reputation in folklore, myths, and modern culture. This is exacerbated by negative media attention following public health warnings and health research.

Read more: Why bats don’t get sick from the deadly diseases they carry

We strongly encourage a more matter-of-fact style of reporting around the risks from bat-borne diseases. You are much more likely to be killed by lightning or by falling out of bed than by a bat.

Granted, the risks posed by bat-borne diseases are relatively new to most of the public, but more nuanced framing can effectively support both public health and wildlife conservation goals. So while you remember to slip-slop-slap, be croc-wise and snake aware, and wear gloves when gardening, you should also add “don’t touch bats” to your common-sense repertoire.

Justin Welbergen, President of the Australasian Bat Society | Senior Lecturer in Animal Ecology, Western Sydney University and Kyle Armstrong, Past president of the Australasian Bat Society | South Australian Museum, University of Adelaide